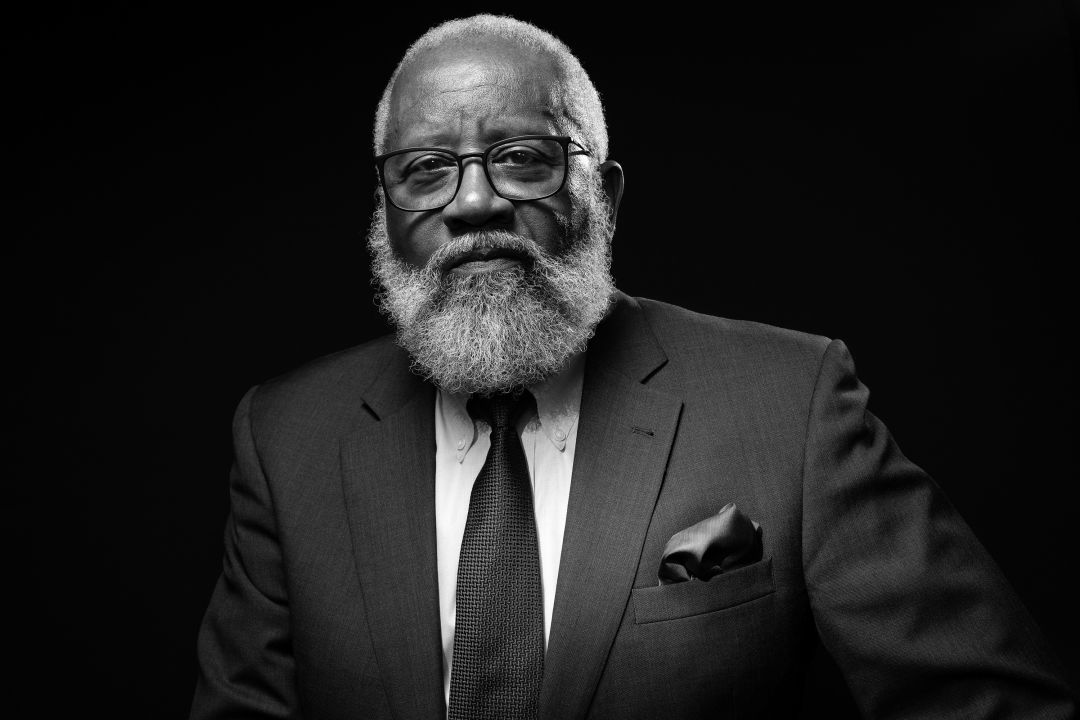

David Wilkins on Reconstruction, Reparation and Black Excellence

David G. Wilkins

Image: Michael Kinsey

Attorney David G. Wilkins has had a long and illustrious career—first as vice-president and general counsel for Union Carbide Corporation, then as vice-president and chief diversity officer for the American Red Cross; and then, for 25 years, as associate general counsel and director of ethics and compliance at Dow Chemical Company, where he was the highest-ranking Black lawyer in the organization. Finally, before retiring to Sarasota in 2018 with his wife of 47 years, Lois Bright Wilkins, he was vice-president and chief compliance officer of Montreal-based SNC-Lavalin Group.

And despite being officially retired, Wilkins still has a full plate. Today, at 70, he teaches courses on American slavery and the Reconstruction Era at Booker High School, at the Association for the Study of African American Life and History’s (ASALH) summer Black History series, and at OLLI at Ringling College. He also serves as president of the Manasota branch of the ASALH, which recently launched a program called the Freedom School, a community-based Saturday school program which aims to improve students' reading and literacy skills as well as teaching Black history. This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Tell us about growing up in Illinois.

“My family is from South Carolina. We were part of the second wave of the Great Migration. Of four boys, my brother and I were the only ones born up north. My folks were determined for us to get the best education possible. My mom had a high school education, and my dad had a seventh-grade education, but they were the smartest and most industrious people you’d ever meet. They realized that we wouldn’t survive long in the south. My father was a strong-willed man with four sons, and he and my mother were fearful for our future.

“Our grandparents had migrated to Evanston, where there’s a long-standing Black community. We had a wonderful childhood. My brothers and I were blessed with wonderful parents and family and encouragement. And there was the ever-present will of my father that we would succeed despite ourselves.

“We lived in Evanston until I was in the third grade. In pursuit of better schools, we moved to a small suburb called Glencoe for New Trier Township High School, which was one of the best public high schools in the country and still is. Glencoe consisted of a small Black community that was embedded in a Jewish community. It had been there for hundreds of years, since the north shore was basically large estates that were served by butlers and maids who built small homes in adjacent communities.”

Was it a racially charged or friendly environment?

“My middle to high school experience was as the only Black kid in class. There may have been two other Black girls in the school.

“As I got older, which was the mid-1960s, early '70s, I was aware of civil rights movements going on . When I compare my upbringing to kids in the inner city, I consider myself blessed, emotionally and socially. Once I left the enclave of family and friends, I realized the difference. There would always be someone challenging me because of the space I wanted to inhabit.”

How about college?

“I attended Wesleyan College, a primarily white institution. I knew that I wanted to go to law school. In fact, there was a family joke that I talked a lot as a kid. I’d hear, 'You talk so much that you’re gonna be a lawyer one day,’ and the label stuck.

"At college, I was looking for something more than the typical curriculum, and it turned out to be an interesting path that I set for myself en route to law school with the help of two white professors, Paul Bushnell and Dr. Robert Bray.

“Paul Bushnell was involved in civil rights and protests; he was a great mentor who introduced me to more Black history than ever before. And Bob was my English professor, who had a great grasp of authors like James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, as well as early 20th-century writers, the Black arts movement, and the Harlem Renaissance. I took those writings and listened to the Black voices of those eras, and I analyzed what was going on in the streets during the civil rights movement.”

How did your career path lead you to working at Dow?

“I joined in 1987, after 10 years practicing private law in Chicago. I was on the corporate ladder, doing legal jobs, and transferring for opportunities. I went to Indianapolis to assist with a joint venture with Eli Lilly, where I worked for a senior executive named Dale Lewis for a couple years. One day, he asked, ‘Why don’t you consider a transfer to HR? At Lilly, we take our great people and transfer them to learn other parts of the company.’ I took the job knowing nothing about human resources. I called Lois and said, ‘You won’t believe what Dale just offered.”

“I learned a lot about what I didn’t know, and I learned a lot about people. At the time, when it came to diversity, Dow was a leader among the large chemical industrial companies, yet we recognized how far behind we were."

Talk more about that.

“What I found interesting was that our international companies had a better grasp on values and differences when it came to diversity than we did in America. This was in the early 2000s, when diversity was not the DEI model it is today. We had to define what it meant. The greatest challenge was the primarily white culture—that's where strides could be made.”

You teach about slavery and Reconstruction. What is often misunderstood about America’s Reconstruction Era?

“Few Americans understand how much Reconstruction captured the essence of everything we claim to be as Americans. During Reconstruction, we had the greatest opportunity to fulfill the dream of multiracial democracy.

“We had a drastic reversal from the previous hundreds of years of history. We said that we were going to end the horrific institution of slavery, and repair [our nation] somewhat by giving truth to the phrase ‘all men are created equal.’ It was our first, best and greatest opportunity to truly realize a multicultural democracy.

“What strikes me is the approximately 2,000 Black local, state and federal officials—from local sheriffs to U.S. senators—who were elected in that period. Had Reconstruction become the norm and not the exception, and were we allowed to flourish, we would be a different society today. Even though that’s an obvious statement, I have every belief that had Reconstruction not been stopped—had Republicans passed the Federal Elections Bill and secured Black voters' rights—it would have eradicated, at the very least, inequality. I wouldn’t say that it would have eradicated racism, but we certainly would have gone much further in leveling the playing field in reconciliation.”

What are the ripple effects we're still seeing today?

“The greatest difficulty that we still have today is ignorance and a continued fear of one another. If what began in Reconstruction had flourished, it would not be notable for Blacks to be successful. It would be part of the expectation of what it means to be American.

“However, a tragic story continues to play out. We've seen it throughout history, and Reconstruction is the clearest example of the white resistance to an egalitarian society. Whether it was after the Civil Rights era, the Obama administration, the Tea Party, or the anti-Black violence that continues to percolate today—that resistance is what has kept us where we are. And it is why, when people ask, ‘Will we ever solve this problem?,’ I am afraid to say that we will not until we can grapple with and accept our history.

“That's also why some people don’t want that history to be taught. It challenges the myth they like to maintain. Some benefit from the fear that’s created and build careers on it. Some make it to the White House on that platform, which is tragic.”

How do you define Black excellence and success?

“Black excellence has always been a part of our existence and community out of necessity, because often our survival depended on that excellence.

"Or you can call it determination. We can go back to the example of my parents. My family moved from the south to the north to the suburbs of Chicago. My parents instilled in us [the idea] that we would have different experiences than we had previously, and that we would have to do our absolute best. I don’t know of a Black family that did not build their lives on that imperative.

“That doesn’t mean that we don’t live in a grossly unequal society. That doesn’t mean that though we might be excellent, enormous, race-based disparities don’t exist."

What would you like your white friends or acquaintances to be doing right now?

“I’d like them to be talking to their white friends and acquaintances, and challenging themselves to examine what they are doing when it comes to allies, skeptics and opponents.

“If my white friends and allies want to be engaged in the work that we are doing for the larger community, then they are in the best position to challenge those in their community who don’t think racism is real, or don’t think certain policies created by governors or legislatures are, in fact, designed to perpetuate ongoing racism.

“The most important work they can probably do is the work I cannot do. I mean that genuinely. I know that there are well-meaning folks out there, and it takes courage on their part to use their platform.

“When you look at history, you will see that there are more good people with goodwill and good intent than the others. As our parents would tell us, ‘Hands on the plow, better days are going to come.’ I credit the ancestors for that.”

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill.