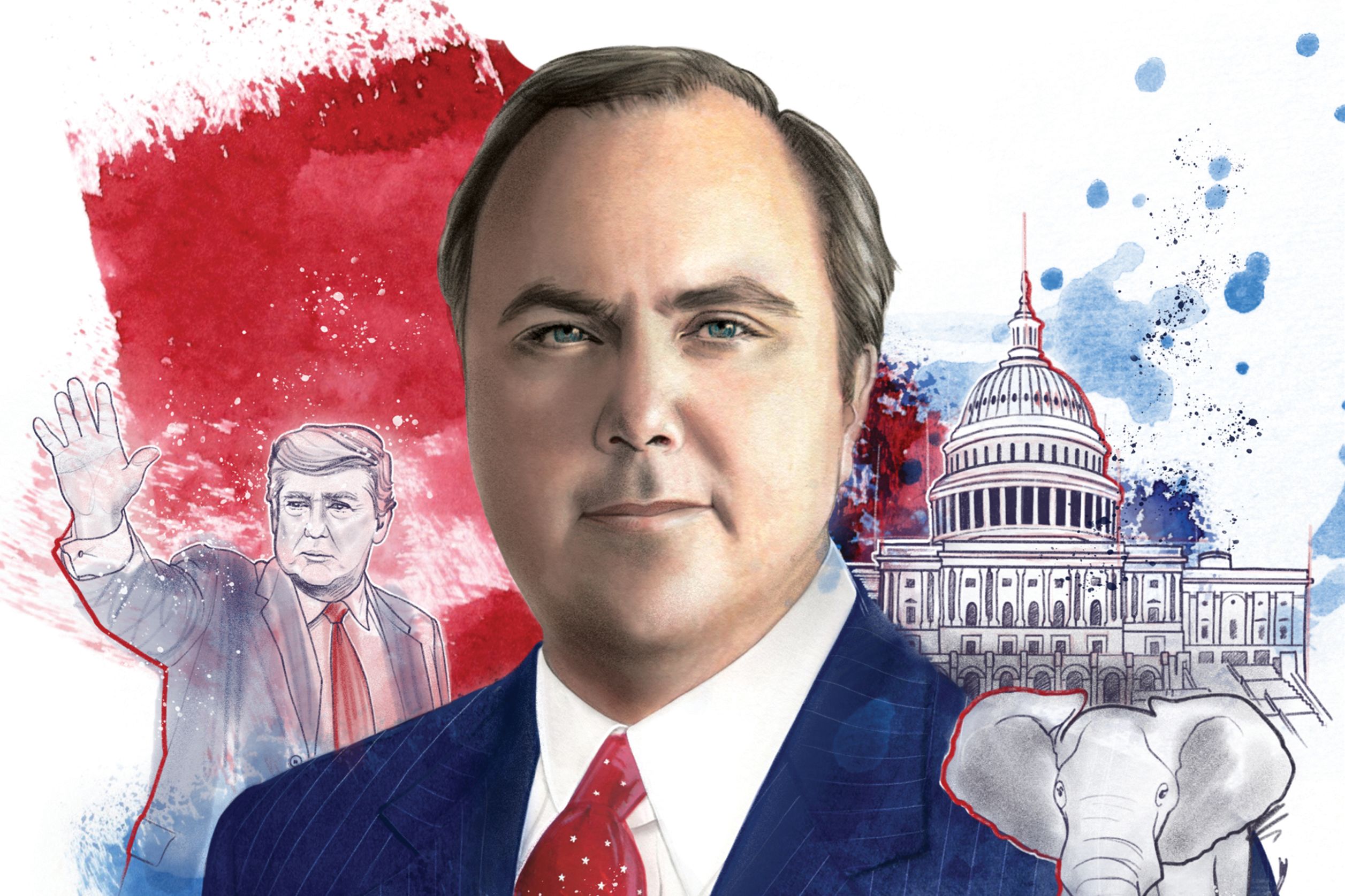

How Far Will Joe Gruters Go?

On the day in late October when the U.S. House of Representatives voted to begin impeaching President Donald Trump, Joe Gruters, the chairman of the Republican Party of Florida and one of the people most responsible for Trump’s 2016 Florida victory, settled into a chair at a small Greek restaurant in Venice.

Gruters, 42, has a thatch of gray hair that contrasts with a cherubic face. In political style, he is nearly the antithesis of the president he admires. While Trump unleashes a torrent of screeds on his opponents, including calling Republicans who have questioned his probity “human scum,” Gruters disdains personal attacks. The harshest criticism that appeared in Gruters’ Twitter posts before the interview was when he referred to Charlie Crist, the former Republican Florida governor turned Democratic Congressman, as a “faux moderate” for voting to support impeachment proceedings.

“Faux? You’re going hardcore French?” I tease Gruters, who smiles good-naturedly.

“What can I say? I’m not an executioner,” Gruters says. “I’ve always been nonconfrontational. I try to bring people together and win them over with kindness. I don’t believe in holding a grudge.”

That style, combined with uncanny political instincts, ambition and an unrelenting work ethic, has fueled a rise to power in little more than two decades that most politicians never achieve in a lifetime. Not only was Gruters elected in 2018 to lead Florida’s Republican Party, he pulls double duty as one of the state’s 23 Republican state senators. Beyond politics, Gruters, a CPA, also co-owns a growing accounting firm. He and his wife, Sydney, have three children, all under 10.

“Nothing that Joe has achieved surprises me, especially in politics,” says Josh Taylor, who has been Gruters’ best friend since their days at Cardinal Mooney High School and who is now public information officer for the city of North Port. “Politics is what Joe has always wanted to do since the day I met him. It’s almost as if it is in his DNA.”

But now, just as he has reached the rarefied air in which he advises the president, speaks to crowds of tens of thousands and wields power both in the state capital and in Republican Party halls across Florida, Gruters finds himself buffeted by political winds he never saw coming. The first and most obvious is the impeachment of Trump. Gruters is not just a Trump supporter. He may be the Original Trumper, withstanding scorn from many in his own party when in 2012 he picked Trump as the Sarasota GOP’s Statesman of the Year. Four years later, with Trump still a longshot in a crowded Republican field, Gruters boldly endorsed him for president over native sons Sen. Marco Rubio and former Gov. Jeb Bush.

Trump’s unpopularity, however, is testing Republicans like no presidency in a generation. Since Trump took office, 100 Congressional Republicans have left office or said they plan to leave, the greatest net exodus by one party since the late 1930s. Gabriel Hament, a rising voice among Sarasota Democrats, thinks Gruters faces fallout if Trump is removed from office. Hament’s views are more than partisan. A decade ago, when Hament was a student at Pine View School, Gruters, then in his early 30s, took the teenager under his wing and helped him get his first internship.

“I have great respect for Joe, who was a mentor to me and who I know cares deeply about Sarasota,” Hament says. “And because of who I know Joe to be, I cannot reconcile that he has gone down the rabbit hole of one of the biggest con jobs ever done to America.”

But Gruters’ bigger challenge this year was in Florida. As state Republican Party chairman, a position he won by a huge margin, he was in a struggle with the most powerful leader of his party, Gov. Ron DeSantis. DeSantis questioned the loyalty of Gruters, who in a rare case of picking the wrong horse, supported DeSantis’ rival, Adam Putnam, in the 2018 GOP gubernatorial race. Gruters and Putnam were longtime friends, and Putnam was the establishment choice. But DeSantis, elevated by an advertising campaign in which he expressed fawning devotion to Trump, turned the race upside down. Another wedge is Gruters’ ties to Rick Scott. DeSantis supporters, who are already positioning him for a 2024 presidential run, see Scott as a potential opponent for the nomination. DeSantis’ press office did not respond to interview requests.

Whatever the motivation, it was glaringly obvious that the governor’s team wanted Gruters to quit his chairmanship of the state party. DeSantis tried to humiliate him, publicly stating he would take half of Gruters’ $150,000 chairman’s salary to give to his handpicked choice for GOP executive director—something the governor knew he had no power to do.

Then DeSantis’ team portrayed Gruters as being impotent to bring in President Trump for a state GOP dinner this fall. While Gruters was said to be calling state GOP leaders to tell them the event had been canceled, DeSantis was simultaneously announcing that Trump, after all, had agreed to come. When Trump eventually visited, Gruters was nowhere to be found. Republican leaders said he had a previous obligation that day involving prisons, which seemed a metaphor for his situation.

“Death by a thousand cuts,” Gruters told me that day at the Greek restaurant in Venice when he admitted he felt like a character in House of Cards.

But Gruters would not—and could not—challenge DeSantis, who in 10 months in office had an approval rating of 72 percent. Instead, he was desperate to show DeSantis that he was completely loyal, even as the media portrayed Gruters as a political punching bag.

“Head down, absorb the blows and do the best job I can,” Gruters recalls. “I didn’t have a lot of options. But one thing I knew, I was never going to resign. Never.”

Then, in early November, state Senate President Bill Galvano of Bradenton, a close ally of Gruters’, brought the governor and Gruters to “sit down and break bread.” None of the participants will say what was said, but that afternoon DeSantis joined Gruters on a conference call with state Republican committee members. The governor said Gruters had his support. A cloud had lifted.

“We put this whole thing to bed,” Gruters says. “All our focus is on getting the president re-elected.”

Joe Gruters with wife Sydney and their three children.

Image: Courtesy Photo

In a city in which most people are from somewhere else, Joseph Ryan Gruters is a rarity: a fourth-generation Sarasotan, whose great-grandfather, William Hobson, moved to Sarasota in 1922 to become the chief tent maker for Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Gruters is one of six offspring of working parents—his father is a computer programmer and his mother is a scuba instructor—who sent their children to the private Catholic schools of St. Martha’s and Cardinal Mooney.

Even as a teenager, Gruters displayed drive and ambition, becoming class president and winning 14 varsity athletic letters at Cardinal Mooney. In 1992, when he was a freshman, his history teacher offered 10 extra-credit points for any student who attended Vice President Dan Quayle’s speech in Sarasota. Gruters showed up.

“I remember the crowd being so excited; it was like a big football game,” Gruters recalls. “I knew from that moment that it was something I wanted to be a part of.”

He joined the Sarasota County Young Republicans, quickly rising to president. He put out yard signs for candidates, worked at rallies and soaked in all he could about what it takes to win an election.

“Joe stood out,” recalls Robert Fottler, a government teacher at Cardinal Mooney High School for 48 years. “He was outgoing, likes people and always had a good sense of humor. He came from a competitive family that also believed in a very conservative strain of Catholicism, which is what I believe shaped Joe’s beliefs more than anything.”

But Gruters faced a daunting obstacle to his political ambitions. He was plagued by a speech impediment that prevented him from pronouncing certain letters. It was so disabling that he was held back in third grade because his parents feared that he would be overshadowed by his twin sister, Jackie, who now works for the CIA. Gruters recalls his mother telling him she would be happy if he graduated from high school. The taunts stayed with him, including classmates who called him “Joe Gouda” because Gruters couldn’t pronounce the letter “r.”

“Up until I was in college, I literally went years trying to avoid saying any words with the letter ‘r’,” Gruters recalls. “I referred to young women as ‘chicks,’ not because I was sexist, but because I could not say ‘girl.’ I was teased about it, which is the reason, I think, that I have developed a thick skin.”

As a student at Florida State University, Gruters sought out doctoral students in the speech and hearing department, who discovered that Gruters’ tongue moved improperly when he pronounced certain letters, a problem solved with verbal exercises. Suddenly, his life changed. Gruters became so confident that he ran for the Florida House of Representatives when he was 20 and 22 years old. He was defeated, but that did not dim his enthusiasm for politics.

After graduation, Gruters was accepted to the University of Florida law school, but Vern Buchanan, whose children attended Cardinal Mooney, told Gruters he would be a fool to study law when he could learn business from him. In 2007, Gruters began working on Buchanan’s first Congressional effort, a longshot effort in which Buchanan defeated two established Republican candidates, Tramm Hudson and Nancy Detert.

Gruters, just entering his 30s, quickly rose to chairman of the Republican Party of Sarasota County, where his genius for spotting political winners blossomed, starting in 2010 when he became the first county chairman in the state to endorse Rick Scott for governor while nearly everyone else was backing establishment candidate Bill McCollum.

“Rick Scott used to drive past Sarasota every night on his way back to his home in Naples,” Gruters recalls. “He called me up and asked if he could meet with me. I knew immediately that day I sat down with him that this guy was going to win. And like Vern Buchanan, he was a great businessman. I always thought being successful at business was a much more important factor in winning elections than political experience.”

In his victory speech, Scott credited Gruters and predicted he would become chairman of the state GOP. Gruters ran for that position, was defeated, but got a nice consolation prize from Scott: appointment to the FSU Board of Trustees.

In the summer of 2012, Gruters made his boldest political call, selecting Donald Trump to be honored as Statesman of the Year. The event was the same day as the start of the Republican National Convention in Tampa, christening nominee Mitt Romney. Trump, embroiled in the birther controversy in which for months he had falsely claimed President Obama was not a legitimate citizen, was considered such a pariah that the Republican Party didn’t want him anywhere near the convention.

But Gruters, who studied polling data, sensed that Trump struck a chord with voters. And like Rick Scott, Trump was a businessman first, not a politician. Trump was difficult to reach, but Gruters kept leaving messages at his golf clubs and hotels. Eventually, Michael Cohen, Trump’s attorney (who later turned against the president and is now in prison), got back to Gruters, and a deal was reached to bring Trump to Sarasota on Aug. 26, the day of the start of the GOP convention, to be honored as Statesman of the Year. Then Hurricane Isaac intervened, and Republicans canceled the opening day of their convention.

Gruters turned the natural disaster into an incalculable advantage for himself and Trump.

“I told [Trump], you have to come, we have an $80,000 deposit at the Ritz-Carlton that we can’t get back,” Gruters recalls. “Trump said, ‘As long as you can guarantee I’ll have a place to land my plane, I’ll be there.’ We drew 1,200 people that night, the largest crowd by far we’ve ever had for the event. We also had a couple hundred reporters who came down because the convention was postponed. To this day, I think that event may have helped give [Trump] the confidence to run for president.”

Gruters recalls writing press releases for the visit and having one after another rejected by Trump’s team because of a lack of superlatives. Finally, Gruters came up with, “Not Even Isaac Can Stop Trump,” which was printed almost verbatim in the local papers. He had won Trump over.

In February 2016, having risen to vice chairman of the state GOP, Gruters endorsed Trump for president when virtually all prominent state Republicans at the time were supporting Jeb Bush or Marco Rubio. An outcry erupted for Gruters to resign. FSU students protested, saying it was reprehensible for a university trustee to back Trump.

Gruters, undaunted, became co-chairman of Trump’s Florida campaign. Late in the race, after the Access Hollywood scandal broke and Republicans distanced themselves from Trump, Gruters took over press relations for the Florida campaign in the pivotal final weeks.

“If Trump lost, I knew I would be thrown out of the party,” Gruters says. “I was hoping that I could get a spot on The Apprentice.” Gruters wasn’t joking. Competing on the show was his fallback plan if Hillary Clinton won the presidency. “Not that I would have gotten it,” he says. “But I definitely had it in mind.”

Instead, Trump’s victory fortified Gruters’ prescience at picking winners: First Buchanan. Then Scott. Now Trump. Three for three on candidates who all started as longshots.

“No one can deny Joe’s ability to read the political winds,” says Kevin Griffith, former vice chairman of the Sarasota County Democratic Party, “and he’s been rewarded for it.”

Gruters with Trump on Air Force One

Image: Courtesy Photo

When Trump was elected, Gruters was in line for a top federal job. He interviewed for several positions, but he and his wife Sydney decided to remain in Sarasota because traveling back and forth to Washington, D.C., would be too hard on the family. And the job he really wanted—ambassador to the Vatican—was never offered. That went to Callista Gingrich, wife of Newt Gingrich.

He was offered a consolation prize, though, when he was one of three men appointed by Trump to the Amtrak board of directors. Nearly a year later, none have been confirmed. The industry publication Railway Age called the picks “crony capitalism” and said Gruters lacked experience and qualifications for the job. Gruters still expects the nomination to go through.

Then, in 2018, another opportunity landed in his lap, when U.S. Rep. Greg Steube resigned as a state senator to run for Congress. Gruters easily won Steube’s seat. And, as a close ally of Galvano, he is poised to make the most of it.

As a legislator, Gruters has taken a hard line on abortion and immigration, but has broken with his party on other issues. He has sponsored pro-environment bills, including banning smoking on public beaches and increasing the punishment for municipalities that release sewage into waterways. After a synagogue shooting in California last year, Gruters won praise from Jewish leaders for his bill targeting anti-Semitism in schools. Gruters also sponsored a bill that prevents workplace discrimination against LGBT workers. That led John Stemberger, the influential president of the Florida Family Policy Council, to demand Gruters resign as state GOP chairman.

Crossing party lines has won him respect. Rita Ferrandino, former chairman of the Democratic Party of Sarasota, says during the height of the Tea Party revolt nearly a decade ago, she and Gruters agreed to a civility pact in opposition to the inflamed rhetoric being spewed by some activists. “We found a way to work together,” Ferrandino says of Gruters. “I respect the guy.”

But while he eschews political bomb-throwing himself, Gruters also sees no problem in embracing some of the most inflammatory factions in his party. He appeared at a rally in support of Roy Moore, the accused child molester and racist, who ran for Senate in Alabama. He is currently leading “Stop the Madness” rallies against Florida Democratic Congress members and is calling for ending the “coup” against the president by the traitorous trio of Democrats, “the Deep State” and the media. His unqualified support for Trump seems to fly in the face of his “can’t we all get along?” style.

“I look at President Trump like I’m judging an Olympic figure skater,” Gruters says. “On the technical aspects, he’s a perfect 10. On the artistry, the way he communicates, he may only get a 5. But it’s the technical part—the judges he’s appointed, the tax cut, and all the other things that he has accomplished that are far more important to me and I believe to most Americans.”

Like most Republicans right now, Gruters doesn’t see his winning streak at risk. He is betting on Trump again.

“President Trump is not only going to get through this partisan attack, he is going to win re-election in 2020,” Gruters says. “My support for the president could not be greater.”

And if Trump loses? Griffith, the former county Democratic Party vice chairman, says, “Joe’s a survivor. I suspect he’ll land on his feet no matter what happens.”

Gruters is looking far beyond survival, however. For now, he says he’s focusing on his role in the legislature and in the state party. But his quest for bigger roles isn’t far away. He’s contemplating running for Congress when Buchanan retires, which Gruters does not expect to happen for eight years.

Few politicians risk sharing their ambitions so nakedly, especially when it involves a job currently held by a mentor. But having bet big on others and won so often, Gruters is ready to follow Buchanan, Scott and Trump to his own place on the national stage.

“That’s sitting out there like a big piece of chocolate cake,” Gruters says of running for Congress. “And I really love chocolate cake. I don’t think I could resist taking a bite out of it if I get the opportunity.”

Illustration by Dena Cooper