Rev. Larry Green Sr. on the Church's Role in the Black Community and the Hope in Helping Others

This article is part of the series Listening to Diverse Voices, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

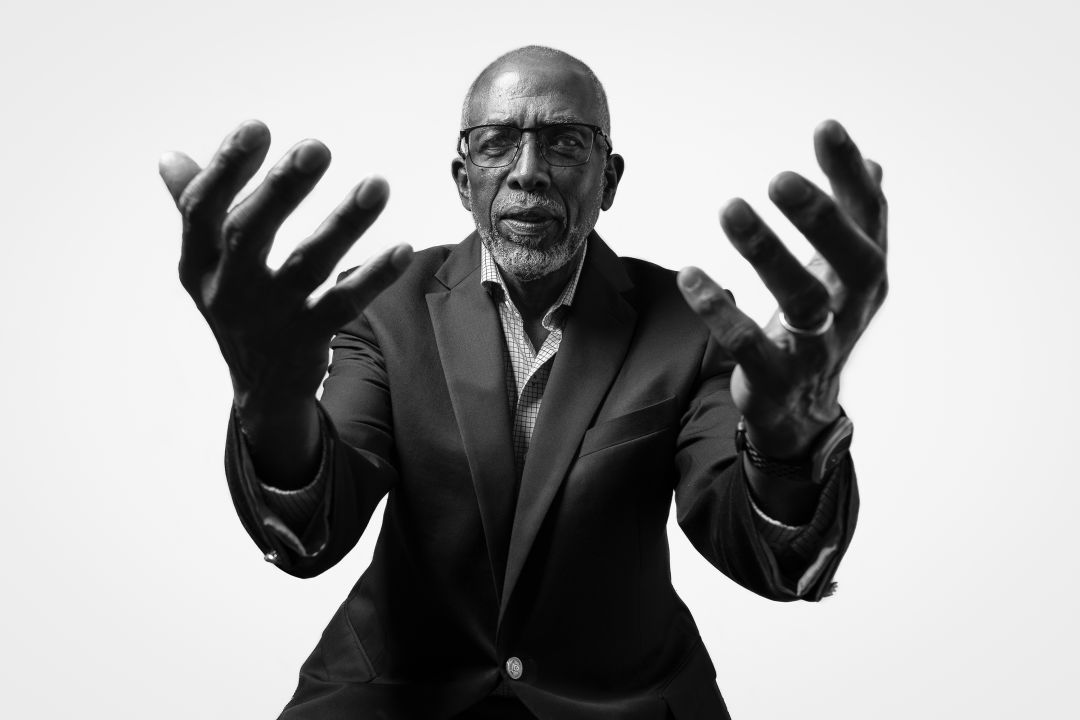

Rev. Larry Green Sr.

Image: Michael Kinsey

Born and raised in a small community outside Richmond, Virginia, Rev. Larry Green Sr. found science before religion called to him.

After receiving his bachelor's degree in biology from Virginia Union University, Green, 77, got his master’s degree in microbiology at Virginia State University. He became the Virginia's first Black hire, as an environmental planner for the state water control board.

It was only later that he entered the ministry, serving as pastor of the First Union Baptist Church of Richmond before relocating to Grace Baptist Church of Waterbury, Connecticut, in 1984, where he remained until he retired in 2013. During his tenure, Green expanded Grace Baptist Church's leadership to include women and young adults; revitalized children and youth programs and contemporary worship services; and oversaw the remodel of the existing church building, which ultimately doubled in size.

A servant at heart, Green’s reach went beyond the church. He was an advocate for affordable housing and served as president of Grace Development Corporation of Waterbury, which developed and operates Grace House, a 40-unit affordable, independent living facility for seniors, and Grace Congregate Housing Corporation of Waterbury, which developed and operates Hearth Homes, a 41-unit affordable housing complex for seniors. Both corporations also developed and operated an adult daycare facility.

His work didn't stop there. Green served as president of the Greater Waterbury Interfaith Ministries, vice-president of the Connecticut State Missionary Baptist Convention, and sat on numerous nonprofit boards including the Western Connecticut Agency on Aging, St. Mary’s Hospital of Waterbury, Waterbury Opportunities Industrialization Center and The Waterbury Foundation.

In 2015, he and his wife of 55 years, Dr. Dorothy Libron-Green, moved to Sarasota.

What was it like growing up in a small community?

“I grew up in segregated Virginia, which means the racists were largely separated from us. I didn't experience the presence of white people too often, because my existence was mostly contained to the Black community from elementary to high school.

“In town, there were bathrooms, water fountains and such that we couldn’t use. And, we’d have to pass a certain seat on the public buses because Blacks rode in the back of the bus.

“It was an environment of separation. My family, and the Black community, shielded us from feeling the brunt of it.”

What was your early education like?

"My first four years of schooling were in a two-room schoolhouse, a Rosenwald school, with one teacher who taught grades one to four. There were two rows for each grade. As we progressed, we’d move from one row to the next. I remember that the schoolbooks that were handed down to us the names of the white students who'd used them before.

“I looked up to and emulated my teachers. During middle school, a military veteran was my homeroom teacher for eighth and ninth grades. He encouraged my interest in science. I looked up to him as a hero. The founder and principal of my high school was also the pastor. Because of the size of my classes—there were only 27 students in my graduating class—we had intimate contact with teachers, staff, and students, which created a nurturing environment."

Do you recall your first experience with racism?

“It was when I was about 10 years old, while my aunt was driving my cousin and me from Richmond to Quinton, the community where we lived. We stopped for ice cream, and my cousin and I got out of the car alone. We were verbally attacked by white young men and told to get out of there—it was an intense anger, and we could feel that they wanted to hurt us in a very real way. We retreated to the safety of the automobile and my aunt. I don’t even remember if we told my aunt about it. My cousin and I recently discussed this and how the painful memories of it still exist. Some other memories we blocked out.

“Another memory was when my teacher, in that one-room school, told us about the Brown v. Board of Education decision. She was crying. She said that it wasn’t always going to be like this. I didn’t quite understand it at the time, but I graduated five years later, and our schools were still segregated. This was likely because Sen. Harry Byrd was a strong segregationist and implemented a number of things to block integration.”

How did your experiences in Quinton serve you as you went off to college?

“I left for college with a relatively positive sense of myself. I felt exceptional in a lot of ways, including in the love there was for me. I chose to attend a HBCU (historically black college or university), Virginia Union University, which had only a few white students and white professors. So it was, again, a predominantly Black environment.”

Tell us how you made the leap from science to religion.

“Even though I grew up with a small Black Baptist church in our community, I was always a reader and loved science. Religion didn’t make sense to me, except for weddings, funerals and holidays. Also, I couldn’t ask questions [about religion] because it was forbidden in some churches. I backed away from it from high school through college, my time in the military and my marriage.

“I was reintroduced to religion while I was working with the Virginia State Water Control Board and my wife was a college professor. Her dear grandmother said, ‘You two are doing so well, why don’t you go to church?’ Since she was such a good-hearted person—not a Bible thumper—and treated me like another grandson, we went. The church we chose was an affirmatively Black and Christian one, and we found it to be a wonderful place with good people. We got involved, became a part of the church, and worked with the youth group.

“I liked that it was a progressive Black Baptist church, led by Pastor Paul Nichols. It was the first in the area to open the deacon ministry to women, which says something about the church and pastor. It also opened my wife and me to things we'd never experienced before. As I became intensely aware of how beat down [the Black community] had become by the racist system, I began to ask questions, dig deeper into the teachings and become part of the diaconate. That’s what put me on this track.”

How has the church historically been a center of strength for the Black community?

"Black people have found healing in religion, even when it was imposed upon them. The church has been a place where Black people find shelter from the oppressive and negative culture around them. The church is more than a building; it’s a community of people and a place of strength, goodness and love. And it aids in times of need. The church is a listening place and a place where people can leave stronger than when they came in.

"In the outside world, a parishioner can be the lowest laborer on the totem pole, but at church, they are ‘Mr. So-and-so,’ or a deacon, sister or brother.

"There’s also the social element outside of the church—such as community involvement, housing development, job fairs and health fairs. While the church is not directly involved in advocating for one political party or another, we recognize the sacrifices made in getting the right to vote."

How do you console the Black community in the face of ongoing violence?

"While I am no longer in hand-to-hand, face-to-face ministry, in the past I engaged in intentional listening. Oftentimes, people need someone to listen rather than tell them what to do. Allowing people to express their anger, frustration and/or sadness can help them find comfort and strength. There’s hope in helping one another."

What would you like your white friends or acquaintances to be doing right now?

"Try to understand and see from a different perspective. For example, I am a part of the Manasota Interracial Book Club, founded by a couple of ladies a few years back, which existed through the pandemic. It’s grown so big that there are now subgroups. The interracial groups are small enough for intimate conversations about a book, racial issues and discussions that range from culture to religions to history and the philosophical. Before this group, I don’t think I ever had a conversation with white friends at such an intense level, which leads to understanding and different ways of seeing things.

"I encourage people to become educated on real-world history and stretch to see it from a different perspective. I know for sure that it will not lessen but enhance them as people."

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill