In 1990, Sarasota Waged War on Thongs, Leading to Outrage, Protests and National Media Attention

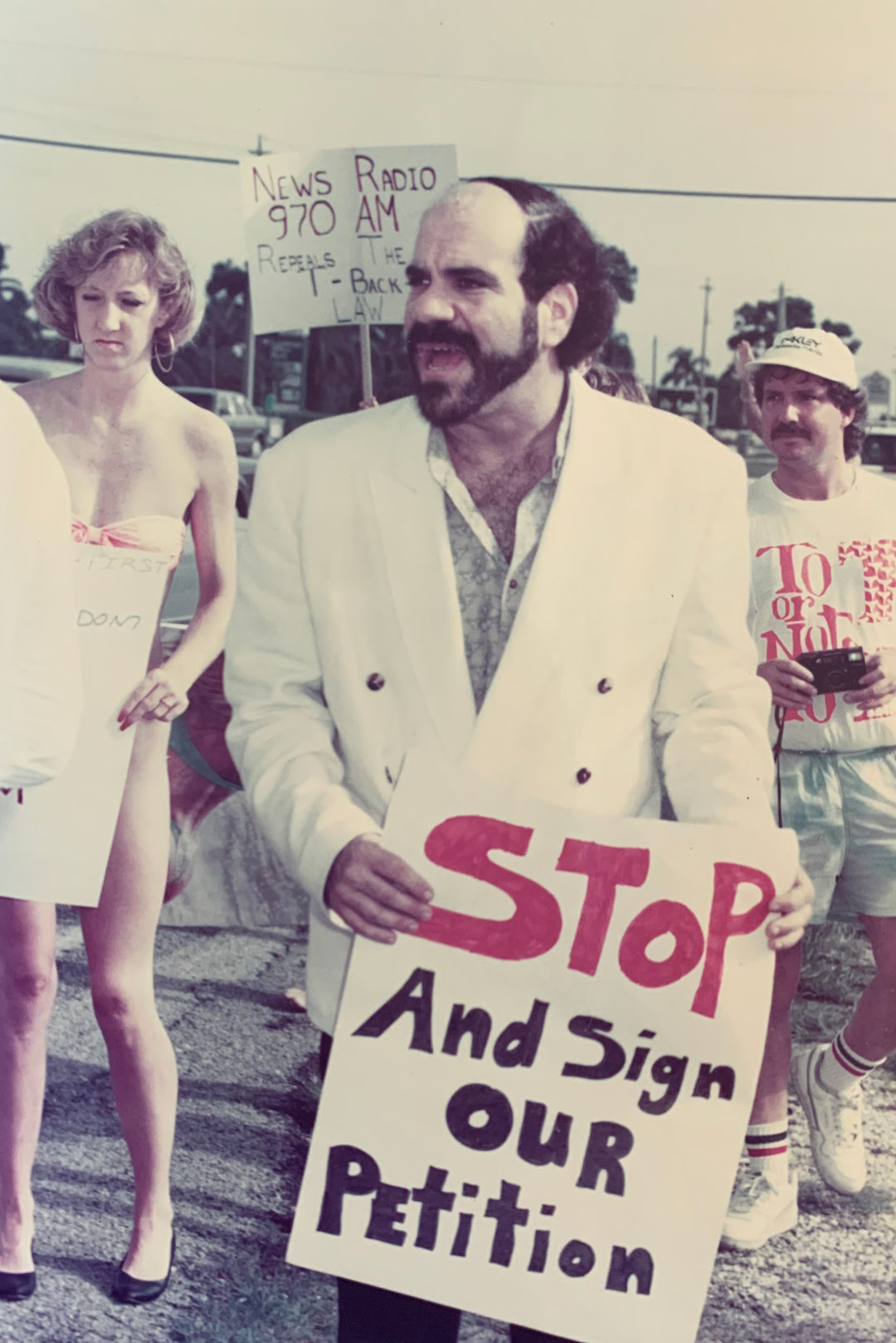

Richard Unger organized protests in 1990 after a handful of residents were arrested for wearing thong bathing suits on Lido Beach.

Image: Courtesy Photo

It all began on May 17, 1990. Germany was in the process of being reunified. The United States had recently invaded Panama. Nelson Mandela had just been released from a South African prison. And a conflict over revealing bathing suits on Sarasota’s public beaches was about to heat up.

Todd Keefe, then 27 years old, was arrested on May 17 on North Lido Beach, along with three other men and one woman. Their crime? Wearing a thong bathing suit bottom.

Although public nudity had not been allowed on City of Sarasota beaches for decades, in 1985, the City Commission made it official, by approving a definition of “naked” that persists to this day. The city defines being “naked” as being “insufficiently clothed,” which means that a person has not covered, “with a fully opaque covering,” one’s genitals or pubic area, “the areola of the female breast” or one’s “anal cleft.”

That meant you weren’t supposed to wear a thong on a city beach. At the time, however, Sarasota police spokesman Russ Nugent admitted that although such bathing suits had been technically illegal for years, the law had not been enforced.

At the Sarasota County jail, Keefe and the others were fingerprinted, photographed, given uniforms and put behind bars. Four hours later, Keefe posted $120 bail and was released. At 10 p.m. that night, he received a call from a reporter at the Sarasota Herald-Tribune asking for an interview.

Keefe, now 60, is a stylist at a salon in Bradenton. He says he assumes that everyone else who was arrested that day was also contacted by the Herald-Tribune, but guesses that he was the only one who was willing to talk.

And talk he did. In doing so, Keefe set off a chain of events nobody could have foreseen. Outrage over the arrests led to hearings at City Hall, street protests featuring men and women in thongs, city commissioners being grilled by Phil Donahue, a feature on Sarasota in People magazine, plenty of hate mail and controversy, and a local rap song inspired by the controversy titled "Don't Ban the T-Back."

Listen to "Don't Ban the T-Back":

“I was going to take the moral high ground if no one else was going to say anything,” Keefe says today. “I didn’t want people to assume who or what we were. If no one else was going to say it, I was going to say that I was a decent person.”

At the time, North Lido Beach was known as an unofficial hangout for LGBTQ+ residents. Keefe is gay, and he and many others believe the principal reason for the crackdown that occurred in 1990 was nothing more than homophobia.

The story goes that nearby residents were complaining about sexual misconduct taking place in the men’s public bathrooms on Lido, but when the police looked into the allegations and found no one there, they moved their investigation to the beach.

Keefe says the arresting police officers wore shorts and posed as innocent beachgoers. “They were looking at us and all of a sudden uniformed cops came out of the woods and started arresting people,” he says. “It was homophobic. It was hidden behind [the claim of upholding] Christian values, but it was plain discrimination. North Lido was known to be an area that was welcoming and OK for us to be wearing what we were wearing. It had been years—10 years or more—that it was a known, relaxed spot for that community. It was unspoken common knowledge.”

After the Herald-Tribune published its story on the arrests, the issue quickly became the talk of the town. Residents split into two camps. Those who supported Keefe questioned why the government should be telling people what to wear and argued that wearing a thong is a victimless crime. Those opposed claimed that thongs would ruin Sarasota’s reputation as a family-friendly tourist town and that seeing people wearing them on the beach would harm children.

Keefe and others wanted the law changed. Four days after being arrested, he appeared before the Sarasota City Commission and proposed the city remove the “anal cleft” portion of its nudity ordinance. According to minutes from that meeting, he pointed out that thongs could be easily found in stores in Sarasota and that it was “misleading” to allow the sale of the suits while not allowing people to wear them on the beach.

The proposed change eventually made it to the City Commission’s official agenda, and on June 4, the public weighed in. According to meeting minutes, Charles Nixon, who described himself as a “Christian surgeon,” told the commission that “God judges and punishes nations and people for immorality. Christians would appreciate the commission taking a stand for morality and decency in Sarasota. The bathing suits are disgusting and outrageous.”

Greg Beauchamp, meanwhile, said that he “couldn’t understand what kind of a thrill it was to expose the crack of your butt to strangers on the beach” and asked, “What right does a man have to show the crack of his butt to someone’s daughter?” Patricia Phebus asked commissioners if they wanted the city to become known as “Sleazy Sota.” Teresa Bernhard merely wanted to “know where they get the term of ‘butt naked.’”

Others spoke in support of the proposed ordinance change, like Carolyn Michel, who said she was “appalled that family values are equated with the amount of clothes one wears.” Today, Michel is an actress who performs at Asolo Rep and other venues. She says she remembers little of the event other than that it was quite the “brouhaha,” but feels the same way today. “Our bodies are just the houses we live in,” she says. “There’s no reason to be embarrassed by the human body. If you go to any European beach, they’re not. Why is the body being sexualized? We seem to not be able to get away from that.” She also agrees the arrest was motivated by homophobia.

Eventually, the commission voted 3-2 against changing the ordinance and the charges against Keefe and the others were eventually dropped. That could have been the end of the story, but it turned out to be only the beginning, largely thanks to one man: Richard Unger, who made sure the controversy persisted until it reached national headlines and daytime talk shows—all by organizing a protest.

At the time, Unger owned Hot Flash, a women’s clothing store on South Tamiami Trail that sold the skimpy thongs that were under the public microscope. When the city declined to legalize those suits, his mastermind marketing skills kicked into high gear.

Just 72 hours or so after the city’s vote, 20 young men and women gathered on the steps of City Hall and bared their behinds at midday, wearing suits supplied by Unger. Publicity ensued, and more came when Unger launched a petition drive over the issue and organized another protest at his shop, this one over a new state rule that banned thongs at state beaches and parks. That protest was filmed and broadcast via satellite as part of a feature on The Joan Rivers Show. The program featured at least a dozen thong-wearing women who wanted to prove the bottoms looked good and should be legalized.

Richard Unger today, near his home in Sarasota.

Image: Hannah Phillips

“It caused car accidents,” says Unger, who is now 70 and still lives in the area. “There was lots of bumper-to-bumper action.”

According to a story in the St. Petersburg Times, Rivers asked then-City Commissioner Gene Pillot, who was opposed to legalizing thongs, “On a serious note, Commissioner, with all the drugs in Florida and all the crime, why are they worried about people in good bodies wearing a little thong bathing suit? I don’t mean to be rude, but it seems stupid.” Pillot answered, “Because a severe problem exists doesn’t mean one overlooks a lesser problem.”

The commotion that Unger stirred up worked. “We sold T-backs like crazy,” he says. Flush with money from all the thongs he was selling, Unger helped Keefe cover his legal fees.

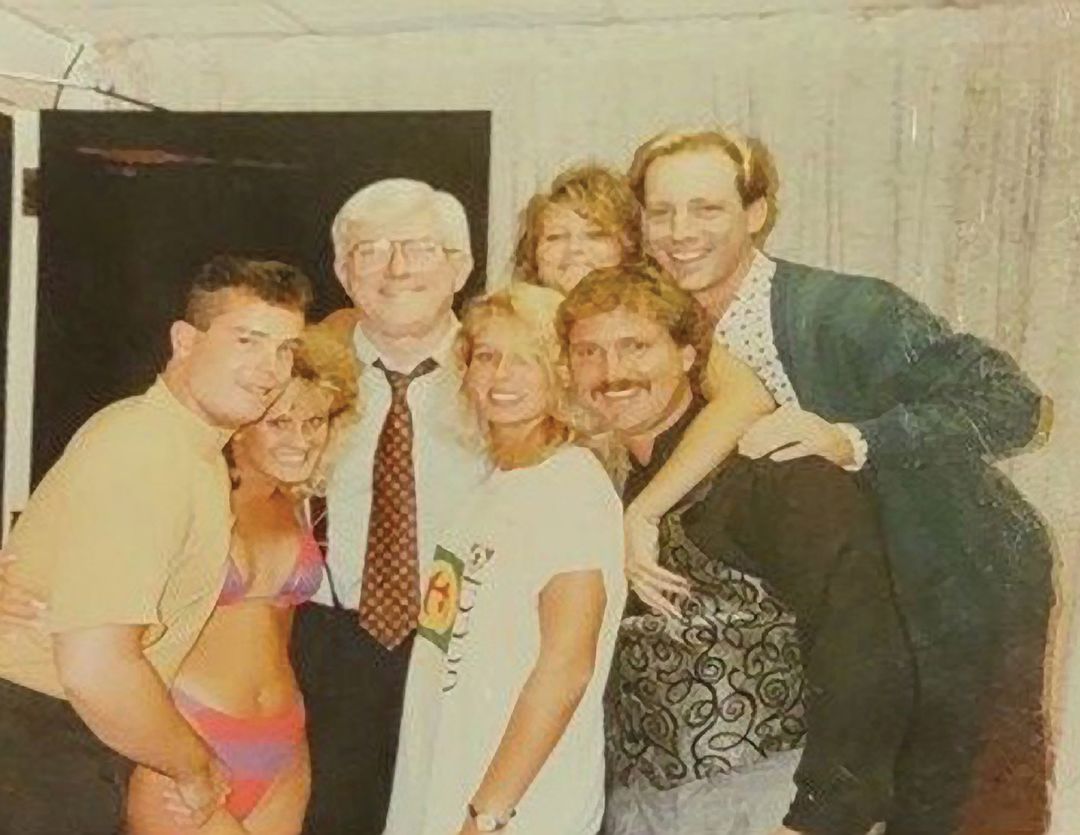

Todd Keefe (far right) backstage at The Phil Donahue Show with Donahue (third from left).

Image: Courtesy Photo

Unger and Keefe were both also invited to appear on The Phil Donahue Show alongside then-Mayor Kerry Kirschner (who argued for a live-and-let-live approach), then-Vice Mayor Fredd Atkins (who opposed loosening the rules) and others from Sarasota. Not only was the controversy moving thongs for Unger, but the episode helped Donahue overtake Oprah in the ratings—no small feat at the time.

“They made me promise exclusivity and said they wanted me before Oprah got to me,” says Keefe. “I was shocked there was so much interest.”

On the show, Unger presented Atkins with a petition with 4,000 signatures from people in favor of allowing thongs, while Atkins maintained that he supported upholding the law as it was written.

“You don’t see any connection between the thong bathing suit and what we would call illegal intimate behavior in a public facility at the beach?” Donahue asked Kirschner.

That’s like saying "men rape women because they have skimpy clothing,” replied Kirschner, who died in 2020.

Asked about the issue today, Atkins says his opinion hasn’t changed, but that, at the time, politics were also at play. “I came from a Christian conservative district and I wasn’t trying to alienate my base,” he says. “It was the most unexpected position I took in my whole career. I didn’t want to go on a show with this junk—an anal cleft issue. But the other commissioners and the Sarasota Chamber of Commerce begged me. Where else would Sarasota get this level of coverage?”

On the show, Kirschner pointed out the irony that Sarasota houses the largest number of Peter Paul Rubens pieces in the country, a collection that includes plenty of bare bottoms. He also pulled out an image of Michelangelo’s David, who may have the most famous anal cleft of all time, and explained to Donahue’s audience in New York City that the sculpture was literally the logo of the City of Sarasota.

“But he doesn’t move around!” Donahue exclaimed, while struggling to properly display a thong to show viewers the roughly inch-wide fabric that was causing such a stir. When a live caller hearkened back to supposedly more moral times in the past, the person stalled when Donahue asked, “How wide should it be to be more moral?”

Reflecting on the situation today, Unger says, “I saw an opening to help those arrested and sell thongs. It was a dual approach we used with media and fashion events. We maxed out our 15 minutes of fame to almost a full year.” As a result, he says, his shop was raided by “every city inspector you could think of to get back at us.”

To the city’s chagrin, the publicity kept rolling in. After Donahue and Joan Rivers, there were two pages dedicated to the issue in the Aug. 6, 1990, issue of People magazine and a segment on The Jenny Jones Show. Keefe even remembers a Japanese media outlet contacting him for interviews.

Unger agrees with Keefe that the motivation for the original arrests “was definitely homophobic. It was an overreach. The cops were only supposed to check out the bathrooms, but then they went to the beach when they couldn’t find anything.”

Today, North Lido is still a destination for the LGBTQ+ community. Earlier this year, an LGBTQ+ travel website called North Lido “the gay beach of Sarasota.” It’s also listed as one of Florida’s top 10 gay beaches by Visit Florida, the state’s official tourism marketing hub and a nonprofit created as a public-private partnership by the Florida Legislature.

More than 30 years after the North Lido arrests, bathing suit styles have evolved, but homophobia remains. In fact, Keefe says, citing a raft of anti-LGBTQ+ laws approved by the Florida Legislature, “We’re going backward fast.”

Sarasota’s nudity law also remains the same. Still, no one seems to raise a fuss over thongs anymore. Unger points out how common the suits were on the MTV reality show Siesta Key. The cast “all wore thongs and no one got arrested,” he says. “No one really cares about this.”

Atkins agrees. “Now you practically see T-backs at the Oscars and on the street,” he says. “I have seen some formal gowns that would be illegal here.”