Samantha Gholar on the Lack of Black Journalists in Newsrooms and the State of Diversity in Sarasota

This article is part of the series Listening to Diverse Voices, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

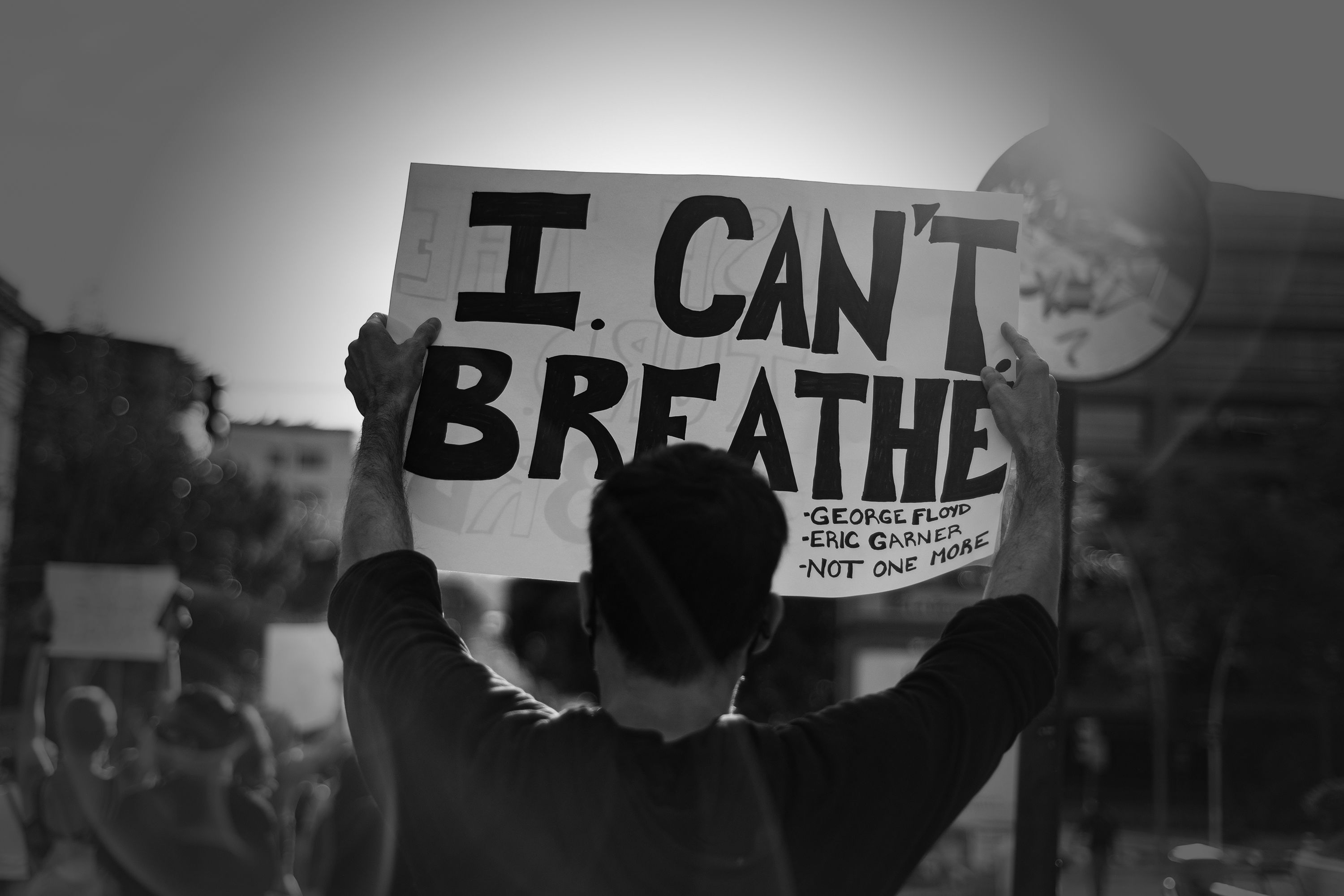

Image: Michael Kinsey

Born and raised in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, Samantha J. Gholar, 38, is a journalist, entrepreneur and certified well-being educator who earned a double bachelor’s degree in mass communications and journalism from the University of Southern Mississippi in 2008.

Because of the Great Recession, after graduation, Gholar spent two years looking for a newspaper job. In 2010, she and her son Jaden moved from Mississippi to Florida, where she landed her first reporter position at the Highlands News Sun in Sebring. She worked as the general assignment reporter for Highlands and Polk counties, covering multiple news beats ranging from crime to city government to sports to the environment. Her work at the News Sun garnered her two Florida Press Association awards.

In 2015, Gholar struck out on her own and began a freelance career that included writing for Sarasota County newspapers as well as providing marketing and business development services. In 2017, she founded Emerge Sarasota, a non-profit, BIPOC-led organization where she serves as executive director. The group is designed to connect young local professionals from ages 25 to 45.

Gholar was hired as the state social justice reporter for Florida's USA Today Network in 2021, where she works full-time writing about topics like Florida’s abortion ban battle, gun reform, police brutality and voting rights. She also contributes to the Sarasota Herald-Tribune and has volunteered with organizations like Children’s First, Boys & Girls Club of Sarasota and DeSoto Counties, and the Alzheimer’s Association, the Gulf Coast Chapter. This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

What was it like growing up in Mississippi?

"I was born and raised in southern Mississippi. I didn’t realize racism existed until first grade.

"I had a great childhood with parents who were in touch with who they were, their roots and the community. I grew up in a Black neighborhood and never felt racism because everyone around us was Black.

"The first time I realized we lived in a racist society was when my mom attended school board meetings every month for at least a year to get the busing routes changed so my little sister and I could go to the white school, because the schools we had access to were decrepit. She succeeded and, in 1991, we were the first Black kids to go to Dixie Elementary in Dixie, Mississippi."

What difference did you notice from an education perspective?

"In second grade, one of my teachers recognized that I was a smart girl. I tested out of that grade and moved into third grade. That’s when things got difficult for me with the white kids.

"I did so well in school, and the white kids noticed. A classmate called me the n-word because I got a higher grade than he did on a spelling test. He leaned over, saw my grade and said, ‘You think you’re smarter than everyone, n-word.’ I went home and told my mom, and she went to that school and raised hell. But I never got an apology, and I saw that kid all the way through high school.

"Shortly after that, I was taken out of three of my six classrooms and placed in advanced placement classes, where I was the only Black student into my high school years. I withdrew from the classes my senior year because it was hard being the only Black student. But that brought its own set of problems—being the smart girl from the advanced classes who was in the regular classes. It was hard to find where I fit."

What comes to mind when you reflect on where you’re from?

"It made me who I am. I couldn’t be any closer to my roots. My grandparents were farmers who worked their own land. I grew up knowing that farm and participating in the harvest.

"The matriarchs in our family live a long time. My maternal grandmother just celebrated her 103rd birthday in February, and her mom was 104 when she died. It’s my lineage."

According to a Pew Research Center survey, only 6 percent of all reporting journalists are Black. What is it like to be one of the few Black voices in this industry?

"I’ve always considered myself a writer; it's innate. I started writing in third grade and won awards for my writing in seventh grade.

"Prior to my social justice role with USA Today, and after George Floyd’s murder, I felt there was no real space for a Black journalist in Florida. I do feel a huge responsibility—especially right now. So many issues [facing Black people] are overlooked because there are no Black journalists in the newsroom.

"The news has been written by white men for what feels like an eternity. Giving [the Black community] a voice is important to me. We are not a monolith— we have beautiful careers and stories and have faced hardships we shouldn’t have to, but still are."

Based on your experience with Emerge Sarasota, what insight do you have for community business leaders who want diversity in their organization but may be falling short?

"It’s odd to hear business owners continue to say they can’t find talented Black workers. I know so many. What business leaders need to do is simply hire Black people.

"So many people of color are passionate about what they do and just want to contribute and lead in this community. It’s frustrating to see so many Black and Latino people get passed over for jobs they deserved. There are organizations in this community that have zero Black or brown people on their boards. It’s unfortunate that business leaders don’t include us in the bigger conversations.

"I have a theory: people of color in business spaces go from ‘pet' to 'threat.’ Meaning, we are wanted as the pretty, shiny diverse person in the office. But as soon as that person starts outperforming the white guy who’s been there for 15 years, they are a threat and have to go. I say: Stop being afraid of us. See how well your businesses do.

"Emerge Sarasota was created because we weren't invited to the table, so we had to make our own. What I would like business leaders to know is that we will do it with or without you. We will find ways to create events and spaces in this community."

The NAACP issued a travel advisory for the state of Florida that says that it is “openly hostile toward African Americans, people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals.” Do you feel safe here?

"I feel safe in Sarasota because of my job, the work I do and the people who know me.

"However, I have a Black son who is 6’6” with a head full of dreadlocks. Racial profiling is very real. We can’t sit here and say it’s not. When he turned 16, two years ago, he didn’t want to drive. When I asked why, his concern was, ‘What if I get pulled over?’

"He only drives in Sarasota, where I know people, because I feel he’s safer in that 10-mile radius. Look, Trayvon Martin was killed just walking home with a hoodie on. I haven’t let my son wear a hoodie over his head since he was 10. Even now, at 18, I tell him to take it down so his face can be seen because he is so tall.

"Most people don’t see my son for who he is—a guy who doesn’t like lizards, who is a good cook, a strong swimmer, the sweetest kid. What they see is a tall Black kid with a hoodie who looks threatening. ‘Big Black kid' and ‘tall Black kid’ are words that began standing out to me in the newsroom back when Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, which was just after we moved to Sarasota. I knew my son was going to be one of those ‘big, tall Black kids.’

"I want people to know that he is worthy of his life and love and respect."

What would you like your white friends or acquaintances to be doing right now?

"I am firm believer in the old saying, ‘You can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make it drink.’ At this point in American history, everyone is aware of the disparities, injustices, inequities and removal of Black history and Black people. It’s been blasted on TV and all over the news. Instead of reading these stories and saying, ‘That’s so sad,’ challenge the system.

"Put the talk to bed and take action. Go to human resources, bring it up in meetings, talk to your uncle who works in a bank. Challenge the system. Be more uncomfortable.

"I want my white friends to do more to make things equitable in every area, from home loans to pay raises.The systemic issues are so deep and so rotten. We can’t do it by ourselves."

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill